An American father shields his son from Irish discrimination. A Chinese foreign student wrestles to safeguard her family at the expense of her soul. A college graduate is displaced by technology. A Nigerian high school student chooses between revenge and redemption. A bureaucrat parses the mystery of Taiwanese time travellers. A defeated alien struggles to assimilate into human culture. A Czechoslovakian actress confronts the German WWII invasion. A child crosses an invisible border wall. And many more.

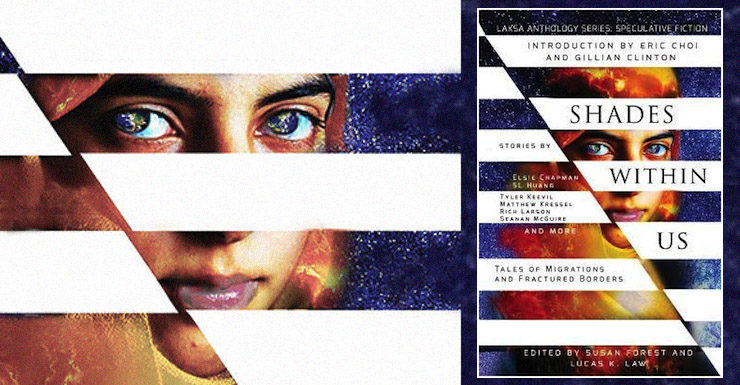

Edited by Susan Forest & Lucas K. Law, Shades Within Us features stories that transcend borders, generations, and cultures. Each is a glimpse into our human need in face of change: to hold fast to home, to tradition, to family; and yet to reach out, to strive for a better life. Available September 8th from Laska Media.

Below, we’re pleased to share both the introduction to the anthology, written by Eric Choi and Gillian Clinton, plus an excerpt from S.L. Huang’s story, “Devouring Tongues.” Other contributing authors include Vanessa Cardui, Elsie Chapman, Kate Heartfield, Tyler Keevil, Matthew Kressel, Rich Larson,Tonya Liburd, Karin Lowachee, Seanan McGuire, Brent Nichols, Julie Nováková, Heather Osborne, Sarah Raughley, Alex Shvartsman, Amanda Sun, Jeremy Szal, Hayden Trenholm, Liz Westbrook-Trenholm, Christie Yant, and Alvaro Zinos-Amaro.

INTRODUCTION

Eric Choi & Gillian Clinton

One of our favourite things in Toronto is a bronze sculpture at the foot of Yonge Street called “Immigrant Family” by Tom Otterness. A man holding two small suitcases, likely containing all the family’s worldly possessions, looks tenderly at a woman cradling a small child in her arms. Their round, larger-than-life faces poignantly express all the fears for the present—and hopes for the future—that have been the experience of newcomers for centuries.

Buy the Book

Shades Within Us: Tales of Migrations and Fractured Borders

Sadly, the warmth and optimism expressed by “Immigrant Family” is sometimes lacking in discussions of migration and borders. Dangerous political persuasions, usually based on a malignant mix of xenophobia and nostalgia, have taken hold in many places. Those who fear the very notion of new people and new ideas coming together often look backward for comfort. “We always look to the past and wish we could return,” says a character in “The Travellers” by Amanda Sun. “We always think things were better in that imagined golden age.”

This is what makes the theme of Shades Within Us so incredibly relevant. Here, you will find twenty-one stories that explore the complex world (and worlds) of migration and newcomers through the unique lens of speculative fiction. The existential threat of climate change is the driver for displacement in “Remembering the Green” by Seanan McGuire, “Habitat” by Christie Yant and “In a Bar by the Ocean, the World Waits” by Hayden Trenholm, while economic upheavals caused by new technology compel the protagonist in “The Marsh of Camarina” by Matthew Kressel to relocate. “From the Shoals of Broken Cities” by Heather Osborne and “Gilbert Tong’s Life List” by Kate Heartfield remind us of the emotional toll that migration can exact upon families. “Devouring Tongues” by S.L. Huang is a parable for newcomers trying to preserve their heritage, while “Porque el girasol se llama el girasol” by Rich Larson could have been ripped from today’s headlines.

Both of us are immigrants to Canada. Coming respectively from Britain and a former British colony, we were privileged newcomers. We never had to cross the ocean in a small, overcrowded makeshift boat. Our lives were never in danger. Over the years, we have occasionally encountered prejudice and discrimination. Sometimes we were called names, or people would make fun of the way we talked, or the clothes we wore, or the shape of our eyes.

But far more often, we experienced and continue to appreciate the generosity and friendship of our fellow Canadians, old and new, and of all backgrounds and ethnicities. Canada has given both of us opportunities that would not have been possible had our parents not made the courageous decision for us to become Immigrant Families. “They leave because they desire to,” writes a character in “Imago” by Elsie Chapman. “They migrate… because it is simply their choice.”

Much has been written about the social, economic and cultural (and culinary!) benefits of migration and open frontiers (a term we prefer to “fractured” borders), but nobody needs to convince us. We see it every day, just by looking at each other.

As writers and readers of speculative fiction, we have an opportunity to help resist nostalgia-based fears. Fiction, and particularly speculative fiction, can do this because it is not just about what is and what was, but what could be. It is more important than ever to try and imagine futures that are optimistic and beautiful. To paraphrase novelist Mohsin Hamid, why must it be called a migrant “crisis” when it could really be a migrant opportunity? The coming together of people from all places and backgrounds could bring a new world into existence in the next fifty or a hundred years that will be magnificent. By being open to new possibilities and not clinging to the past, we may finally embrace all the different shades within us.

DEVOURING TONGUES

S.L. Huang

You come into the sharehouse bone-weary. Slip off your shoes and socks, press your bare toes into the ridged tatami floor. The mats are old, the fabric edging shredded at the seams, but they feel clean on your soles after standing swollen in your shoes for so long, hour after hour stocking cheap snacks at the konbini.

Your thin futon is folded in half so it doesn’t take up the whole floor. The Reaper lounges on it, his black-gloved fingers trailing against the tidy blankets, the fingers unnaturally long and curved—sharp talons even through the leather.

“What do you have for me today?” he asks.

You have to think to answer in English. You’ve been speaking Japanese to customers so long it wants to spill out by reflex. That’s good, you remind yourself. That’s good.

“I need to be more natural,” you say, stumbling over the combination of consonants in the word. “The okyakusama ask me question, and I freeze. I freeze.”

“Questions,” the Reaper corrects, and you can feel your face going hot, the blood rushing in. Akaku natteru, you remind yourself. The word comes slower in English; you think bosh and bush before remembering blush.

The Reaper draws himself up into a spindly skeleton cloaked in black, like melting in reverse. “Say it again.”

“The okyakusa—the customers. They ask me questions, they—I can’t think when they stare. I’m worried I get fired.”

If you lose your part-time job, you will be lost. You cannot ask your family for money like some of your classmates do, whenever they want to go shopping in Shibuya or take a weekend trip to sightsee around Mount Fuji. Your family expects you to be the earner, once you have been accepted into a good college in Japan and are fluent in four useful languages. They brag about you back home: Our daughter always studied English too much, straining her eyes on those books. She wants to work in international business. So much English in her head—it must be why her Chinese essays are so poor!

They think they are boasting while being appropriately humble. They don’t know how right they are.

You wanted to go to college in America, make your English smooth and fluent like the flashy, brash actresses in Hollywood TV shows, but the visa didn’t work out. Immigration laws and the reality of stacking costs narrowed your choices still further. Tokyo seemed like a good opportunity… but you are in limbo now, trying to stuff your head with a fifth language in only two years so you can pass the entrance exams for university, working the maximum hours your student status allows, your budget just barely stretching to cover language school tuition and rent.

You need the Reaper. You can’t afford to fail in your classes.

You can’t afford to be good in your classes. Your Japanese has to be more than that. Natural. Effortless. You have to swallow this tongue whole, so you inhale meaning and blow out answers until you shine at your eventual university. And once you have your degree, you will have such a wealth of choice, you will find a good job, a stable home to settle in—and you will be able to move your family too, somewhere they can follow their hearts without yours pounding with worry about what will happen if they catch anyone’s eye.

The places where that is true seem to be shrinking rather than growing. But you will buy this liberty with your education if you have to squeeze your way into the last free country on Earth.

This is why you summoned the Reaper. What he takes hurts, but two years is not so long. Not so long, you tell yourself. You will not lose too much.

He has crossed the narrow floor, hot and close. He leans his head in to you, the cowl of his cloak hiding a deeper black within.

“Feed me,” he purrs. “Trade me. A word for a word.”

“Don’t take too much,” you hear yourself say, your breath a thread.

“Only what you need. Only what you ask for.”

“None of the English,” you remind him. Your English is still not good enough. You need it all.

“I promise, my dear,” the Reaper says, and bends down for a kiss.

You close your eyes because it is easier than seeing nothing. You feel his face on yours, the dry, cold edges of a mouth, cracked and sharp. His tongue worms in between your lips, forking and suctioning and choking you until you gag.

You can feel him scraping at the insides of your skull. Concepts flow slippery as silk, images and scents flickering through your consciousness: green onions frying in oil, laundry flopping onto the drying rack, the sun filtering through the dangling fronds of your mother’s houseplants and dappling the half-inked drawings spread across her table…

You’re struggling against him by the time he breaks away. His tongue slithers out of you, and you stagger back, retching. Your throat is raw and sore.

You turn your face away. You hate that he sees.

He will not leave, of course. You called him, and now he haunts you. He will lounge in your small, hard desk chair, sated, while you curl on your futon trying not to reach for the memories.

They’re just as sharp and clear as before. But when you see the green onions, you think cong and cung and negi, but in your birth tongue, your mother’s voice, you only find a blank.

Tomorrow, your Japanese will be better. Your teachers are always impressed with how fast you progress. You are such a “majimena gakusei,” they say—so focused, studying so hard.

The Reaper gives as well as takes.

Excerpted from Shades Within Us, copyright © 2018.